So, that Pre-Tolkien Challenge, how does it work ?

First, its entire title is "Pre-Tolkien Short Story Challenge". Then, quite simply, the idea was to pick up three stories (short stories, and fantasy ones, of course) published before the first edition of The Lord of the Rings in 1954, and review them with emphasis on their similarities (or lack thereof) with Gollum's daddy's own writings, without forgetting to aboundantly source them so they could easily be found by the curious reader.

And of course, to share said challenge ; so, bloggers of all persuasions and languages, I strongly encourage you to join us on our journey and to share your own "three tales of swordsmanship and wizardry from before John Ronald Reuel Tolkien".

To me, such a challenge is all the more entertaining that my very basis as to what fantasy is can be summed up in a word : Beowulf. And, as many of you may know already, The Hobbitt is more or less a fairytale retelling of Beowulf (I grossly simplify, here, but you get my point). In fact, I'm in the exact opposite case as to what the challenge was made for : the idea is to present stories made before 1954 to readers not familliar with the period, and I precisely don't read anything (or almost anything) that has been published after the 1950s. That's the very subject I dedicate this blog to !

Tolkien has created what is known as high fantasy. Fantasy as a whole existed before that, and not only as medieval romance or fairytales. Novels like Gulliver, for example, prefigure what the genre would become - with the very distinct particularity that "fantasy" induces the notion of a world created beyond the one of its author, and Jonathan Swift and his character were contemporary (I mean, if you follow that logic, Homer or Shakespeare were also fantasy writers).

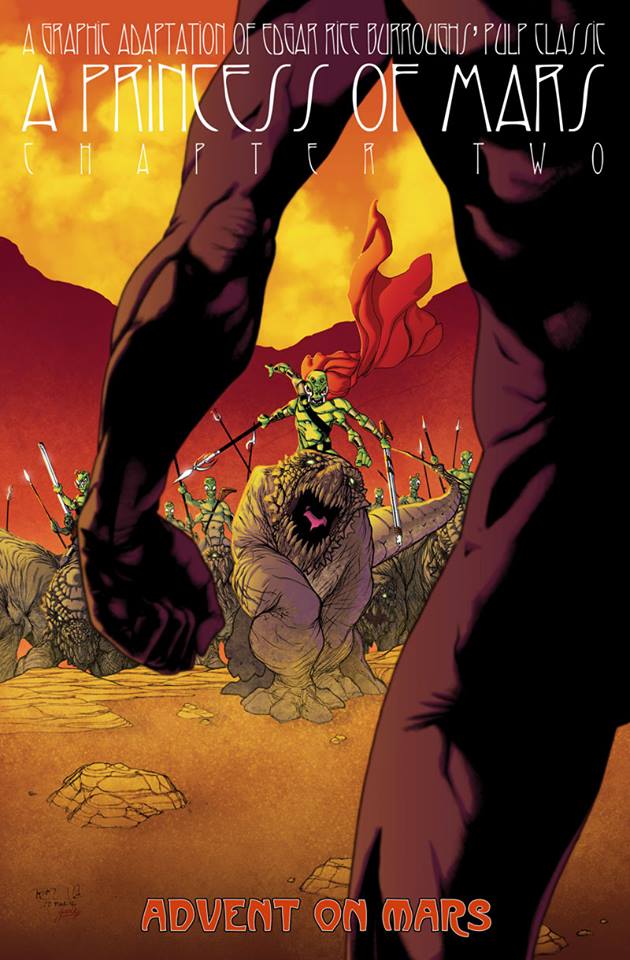

You don't have to go back that far, anyway. Modern fantasy didn't wait for Frodo and his friends. We usually date its birth by the end of the 19th century, under the pen of british authors George McDonald, Lord Dunsany and William Morris (to name the more famous, but you could had Walter Scott or Henry Ridder Haggard as close relatives). In the early 1900s, books like Peter Pan or The Wizard of Oz would popularize "medieval fantasy" stories to young readers ; Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber's sword and sorcery, a staple of early-20th century fantasy, is but a small part of all the stories and worlds that would populate the blossoming genre. One could also had T.H. White, of which Disney would adapt its Sword in the Stone, or Edgar Rice Burroughs, Leigh Bracket and Otis Kline's sword and planet sub-genre to the party.

So, yeah, that's a lot of things. But what about my three stories ?

I've chosen them based on very clear differences from Tolkien's work, whether it be the stories entry point, its world itself, or simply other writing methods - in that, I hope to propose a varied selection, with disrepencies identifiable enough not to have to explain them too much and rather give you the desire to read them for yourselves.

Now, the most important part of the challenge being short stories, which authors can we turn to ?

It's something quite peculiar in the current (precisely post-Tolkien) fantasy industry where almost all stories seem to come as tri/penta/decalogies, but short stories were the norm in the early 20th century. Serial format and magazines were not really the best place to publish lengthy sagas, and amidst the tellers of pulp tales, you'll be spoilt for choice.

I've decided to bypass early classics such as Dunsany or Morris which are certain to be part of other blogger's (certainly more apt than me to talk about late 19th century stories) lists, and to leave obvious pulp authors such as Bob Howard, Clark Ashton Smith or C.L. Moore on the side (mainly because I've already written about them on this blog - on french articles that I've not translated, sorry).

So...

But, The Ship of Ishtar is a 300 pages long novel, not a short story. Lucky for us, Merritt was proficient in the brief exercise ; in such tales, he tends to be poetic, his heroes are lost and his creatures ethereal, halfway between our harsh world and a clouded dream. The first one to be published is the first of my selection : Though the Dragon Glass (1917), reported tale of an extraordinary journey through the looking glass of a chinese legend, brief and confused jaunt in a world of reincarnation and mystic beasts, recounted with awe and disbelief. No swords nor sorcerers here, but a literal divine presence. And, between heavy allusions to the story of Odysseus and the sirens and the escape from Eden, one of the most proeminent trope in early fantasy : the "transported hero". It is, for example, the basis of almost every Edgar Rice Burroughs tale, who was a great admirer of Rider Haggard and Lord Dunsany (and you'll have traced the parallel towards Oz, Neverland and Wonderland yourselves). Merritt would use this method in many of his works ; from The Moon Pool to The Face in the Abyss, from The People of the Pit to the Dwellers in the Mirage, almost all of his heroes are transported men. They then become our eyes and we discover, at their pace and with their own bias, an unknown (an forever partial) universe.

Being a framed narrative, told though the eyes of two narrators, Though the Dragon Glass is more akin to The Hounds of Tindalos than Sigurd and Gudrún, and, precisely, we were in 1917, eleven years before Cthulhu (by the way, Lovecraft never missed the opportunity to claim how he liked Merritt's work), twenty before Bilbo, and whatever the long list of forerunners I've layed on you as an introduction may tell you, there was still a lot of Dragon Glasses to go through and a lot of new universes to visit. Which is timely, because Merritt, a prolific writer, had a lot of fixations (the explorer in search of unknown civilizations, the occult, the undying effect of past knowledge, the struggle between Light and Darkness...) which would inspire a lot of other writers.

First published in the november 1917 edition of All-Story Weekly, Through the Dragon Glass was later compiled in many anthologies, dedicated to Merritt or to the fantasy genre ; anthologies you... don't even have to bother finding. Fallen into public domain in the United States (as it was published before 1923), you can freely read it on the Project Gutenberg website.

You want the guy that has made/been the link between Robert E. Howard and J.R.R. Tolkien ? His name is Lyon Sprague de Camp. Quite a controversial figure, "Sprague", as he prefered to be called, is more often presented as an editor, having republished all the Conan tales in the late 1960s and, according to fantasy folklore, put the barbarian (and the whole heroic fantasy subgenre) back on the map. Trouble is, he did so with "posthumous collaboration" from him and Lin Carter, reworking old stories and finishing uncomplete ones, making him the obvious (and jusfified?) target of many Howard fans since. Even more troubling is how this editorial work completely overlooks his writing one, especially since Sprague is one of the most prolific authors of the 20th century, his carreer spanning an impressive 59 years between 1937 and 1996.

Yet, even there, he is more known for his howardian pastiches, pulpy and almost anarchonical tales published in the middle of the golden age of science-fiction, as is the case of the one that concerns us here : The Eye of Tandyla (1951). It is part of Sprague's Pusadian cycle, heavily inspired by Howard's Hyborian age, and works almost like its quintessencial example. Not that Sprague was a particularly talented writer (although Lest Darkness Fall still stands as one of the best examples of post-WW2 fantasy), more that he perfectly understood and assimilated what made these stories great, and made him want to write in the first place. The Eye of Tandyla is fun (not parodic nor humoristic, don't confuse), a wild adventure with a purposefully thin plot, used as a mean to chain a series of flamboyant twists. The desert is an ever-present background, middle-eastern temples too, and everything bathe under the burning sun of a mesopotamian pseudo-antiquity.

That backdrop, with its unpronounceably named and bloodthirtsy deities, is what made sword and sorcery tales so compelling in the early 20th century, at a time were the middle-east was "reopenning" to westerners (mostly scientifics and adventurers) after centuries of ottoman regime (and a few other things, but we won't delve into the details here). Reports of spiced, dusty and sunburned discoveries flooded papers at the time and, as I've handicaped myself by forbidding me of selecting any of the great names that roamed the famed pages of Weird Tales, Sprague appears as the perfect time-traveller, writing, a mere three years before The Lord of the Ring would change the game forever, stories as they were written twenty or thirty years before : simple and unbridled pulp (he would continue afterwards, too, with his Novarian cycle during the 1960s and 70s). I don't think I need to further explain how and why that fantasy differs from Tolkien's, but if I add that Sprague, an engineer by trade and an avid popularizer of science, created his worlds with all the analytic knowledge he could to, in his own words, "remove any imperfection", relying on actual geographic and anthopologic research (see his study Lost Continent (1954), where he dissects the Atlantis mythos and which countains, quite appropriately, a part of his preliminary work on the Pusadian cycle), the approach doesn't seem that far off, either...

After its first publication in the may 1951 volume of Fantastic Adventures, The Eye of Tandyla was most prominently reedited in The Tritonian Ring and Other Pusadian Tales (Twayne, 1953), and most recently in the de Camp omnibus collection Lest Darkness Fall/Rogue Queen/The Tritonian Ring and Other Pusadian Tales (Gateway, 2014). I've personnaly discovered it in Time Untamed (1967), an anthology selected by Ivan Howard and Isaac Asimov.

And finally, a french one. Oh, no chauvinism at work, here, there's a really interesting point behind that. I have worked on the idea of a french pulp fiction in the past (an article I've been planing on expanding and translating, in case you're wondering), so I obviously had a few tales of sound and fury up my sleeves, but the french fantasy landscape is a very intriguing one. You see, and that's quite easy to forget now that the genre is indeed popular and most of its readers have seen the Peter Jackson movies early on, Tolkien hasn't been translated in french before the turn of the 1970s. 1969 for The Hobbitt and 1972-73 for The Lord of the Ring, precisely.

That is a long time.

I won't cheat and choose anything that has been made in that strange period between 1954 and 69, though, first because I honestly don't know any french fantasy story from that period (seriously, not a single one!), but more importantly, because there was something and someone in the early 20th century that I found particularly interesting to explore : J.H. Rosny aîné and his prehistoric tales. You might know him (although not his name) by the 1981 movie The Quest for Fire starring Ron Perlman, and I could have easily picked the eponimous book from which it has been adapted, but in the interest of an "extraordinary story", I'll go with The Giant Cat (1918). The Giant Cat is many stories in one, starting with the impossible taming of a saber-toothed tiger, continuing with the discovery of strange new territories and ending with the evolutionary war between nearly extinct troglodyte humanoids and a more evolved tribe of fire wielders. Note that, if Though the Dragon Glass is a meager 16 pages long and The Eye of Tandyla less than doubles that, The Giant Cat is a far more substantial effort, reaching, with its 140 pages, novella status.

Rosny's work has the particularity of crossing between fantasy, "fantastic" and science-fiction, spanning several hundred millions years in a long prospection into human history (in an approach that is called "anticipation" in french, which you might roughly translate by the broader "spectulative fiction"). It would thus seem easy to see similarities with the way Tolkien worked the many Ages of Middle-Earth, but where Bilbo's daddy was a english scholar, working his many stories from literary and linguistic research (and Sprague, as we've established, tried to use a scientific method), Rosny's approach is purely historical (please note the italics). His prehistoric heroes are meant to be as close as possible to the knowledge we had of actual paleolithic and neolithic cultures and people at the time (to the point where The Quest for Fire has been studied in the history classes of french elemantary schools for almost 60 years). From a narrative point of view, it's a small detail, as Rosny still had to invent the stories he told, but from an editorial standpoint, it's crucial. See, the french fantasy landscape of the 20th century would be comprised almost exclusively of "historical" novels. Think The Man in the Iron Mask (Arthur Bernède, 1930), for example, and many books in this vein that were all derivatives of the serial format of the great successes of 19th century - The Three Musketeers, The Hunchback...). What was then called "merveilleux fantastique" (literally "wonderfull fantastic") was reserved for young readers, giving birth to a production akin to what the Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan were in english-speaking countries (books like Les Contes du chat perché or the Père Castor collection, of which, sadly, none were translated). Editor Marc Duveau, in the preface of L'Epopée fantastique (literally "The Fantasy Saga", again, never translated) in 1978, attribued this to 17-18th century thinkers, the Lumières, who had turned epic medieval figures and fantastical creatures into ridicule, cimenting french literature into a "cartesianist" rather than "imaginative" state of mind. Conan, for example, would only be translated in 1980, and it is very revealing to look for french fantasy top10s on the internet, discovering in the reading habits of its own fans that the genre as only really existed in France for little more than thirty to forty years. Its most proeminent authors like Pierre Bottero, Jean-Philippe Jaworski or Serge Brussolo have been born in the 1950s, after the democratization of the paperback format (or "livre de poche", literally "pocket book"), which will be the main mean of "liberation" for genre literature in France. To get back to our subject, prehistoric novels have more or less had the same place in french fantasy as pulp sword and sorcery did in the United States : mythological, barbaric and fantastical tales predating a more medieval-inspired outbreak, the fantasy genre having reincorporated and digested its fairytale and legendary origins.

Published in the Lecture pour tous ("Reading for all") magazine during 1918, The Giant Cat was first translated in english in 1924, and republished on paperback as Quest of the Dawn Man in 1964 by Ace Books. You could still quite easily find these paperbacks, but I'd recommend the newer version, under the title The Giant Feline, published in 2010 in Helgvor of the Blue River (another very good prehictoric tale) by Black Coat Press. Alternatively, Rosny's works being public domain in France, you could also read it online (and superbly illustrated)... providing you can read french, of course.

And there you have it. Three tales of very different origins and styles from the time when The Lord of the Ring didn't exist. Three tales you'll have to read to make up your own conclusion(s) on the evolution of the fantasy genre.

Of course, I could have cited many others, so, for the more curious (and quite hungry) of you, I would like to recommend every other book by Abraham Merritt, and, if the "transported hero" question bugs you, go back to Lord Dunsany (who would transport himself) or to Edgar Rice Burrough's Barsoom saga, or read Sprague's Lest Darkness Falls (the story of an american archeologist transported to ancient Rome during the barbarian invasions). If you enjoyed the Pusadian cycle, of course dive into Robert E. Howard's Kull and Conan stories, read of Clark Ashton Smith's decrepit continent of Zothique, or visit the vast streets of Lankhmar in the Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser stories by Fritz Leiber (a contemporary of Sprague who would, incidently, coin the very term sword and sorcery). And as far as prehistoric tales go, it's not pre-Tolkien, but... Jean Auel's Earth's Children saga.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire